A certificate is used to guarantee trust

between two parties during a transaction.

For example, when a user tries to access a web server,

TLS certificates ensure that the communication

between the user and the server is encrypted

and the server is who it says it is.

Let’s take a look at a scenario.

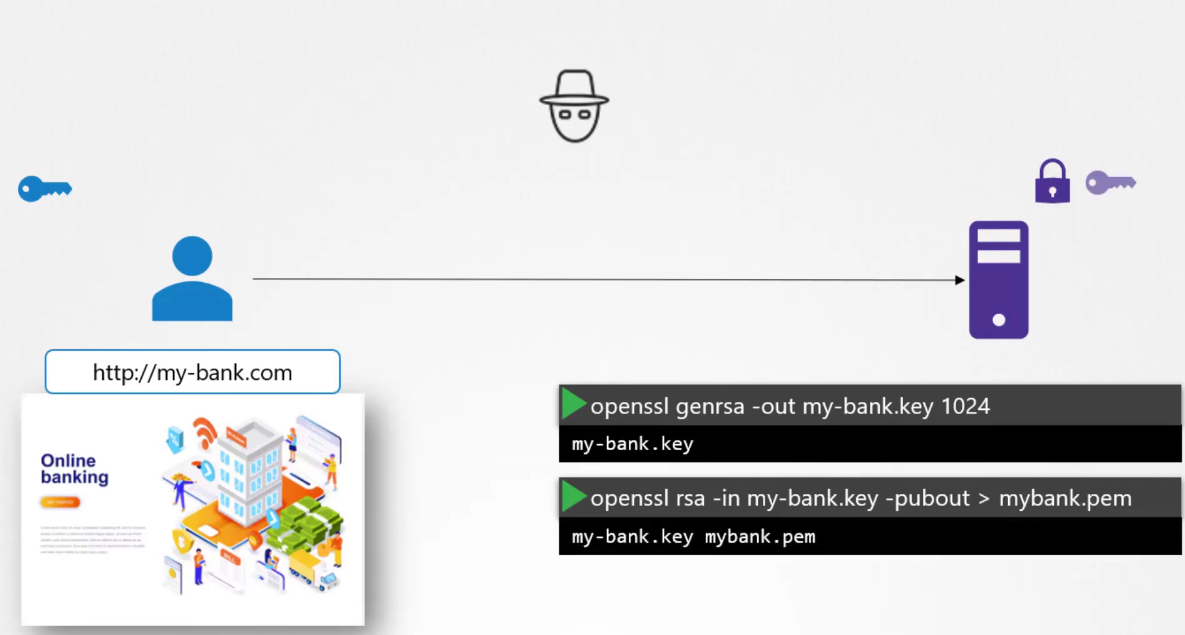

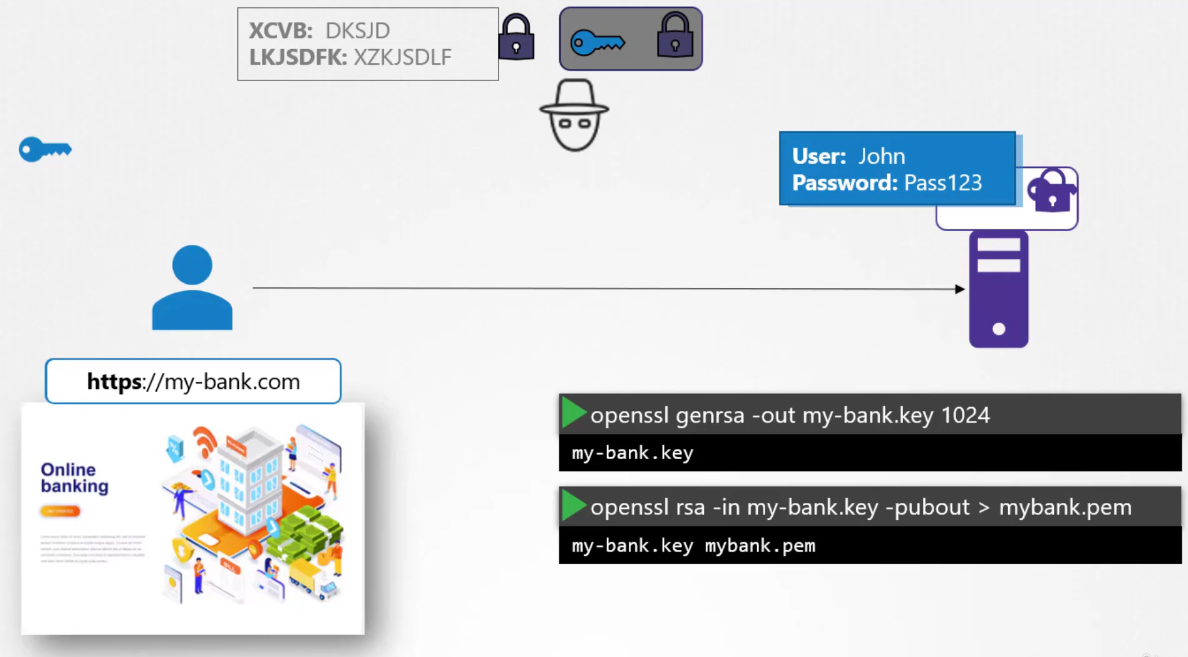

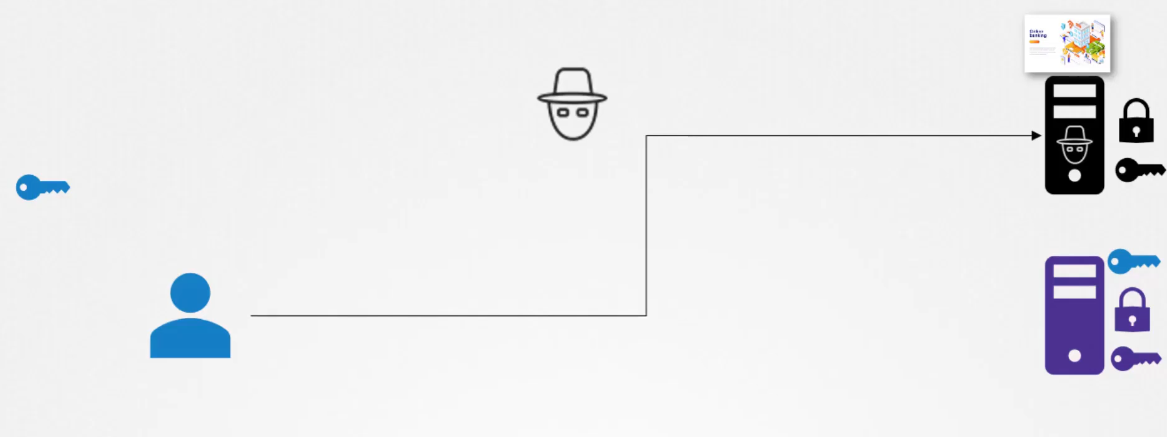

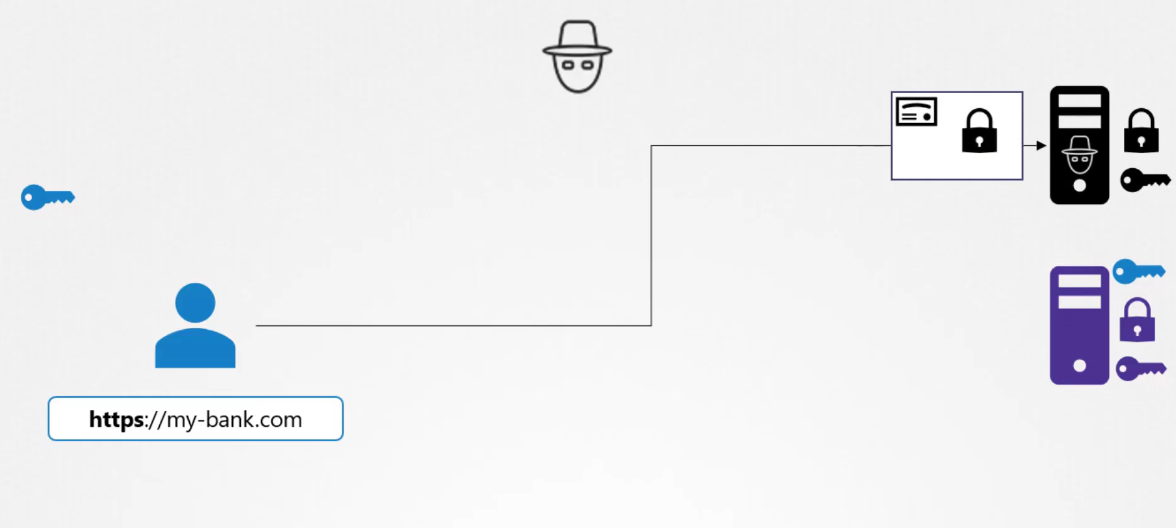

Without secure connectivity,

if a user were to access his online banking application,

the credentials he types in

would be sent in a plain text format.

The hacker sniffing network traffic

could easily retrieve the credentials

and use it to hack into the user’s bank account.

Well, that’s obviously not safe,

so you must encrypt the data being transferred

using encryption keys.

The data is encrypted using a key,

which is basically a set of random numbers and alphabets.

You add the random number to your data

and you encrypt it into a format that cannot be recognized.

The data is then sent to the server.

The hacker sniffing the network gets the data,

but can’t do anything with it.

However, the same is the case

with the server receiving the data.

It cannot decrypt the data without the key,

so a copy of the key must also be sent

to the server so that the server can decrypt

and read the message.

Since the key is also sent over the same network,

the attacker can sniff that as well

and decrypt the data with it.

This is known as symmetric encryption.

It is a secure way of encryption,

but since it uses the same key to encrypt

and decrypt the data, and since the key has to be exchanged

between the and the receiver,

there is a risk of a hacker gaining access to the key

and decrypting the data,

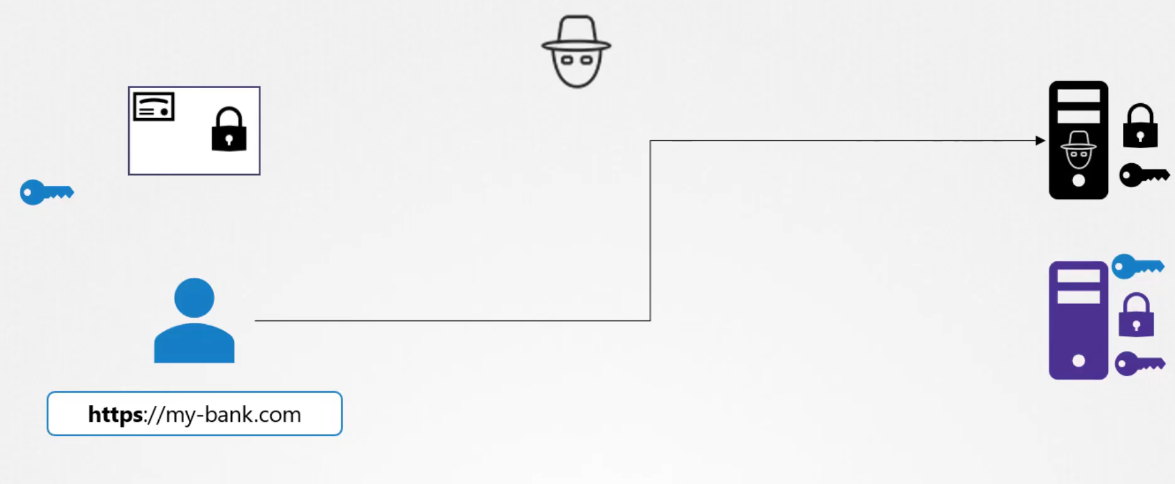

and that’s where asymmetric encryption comes in.

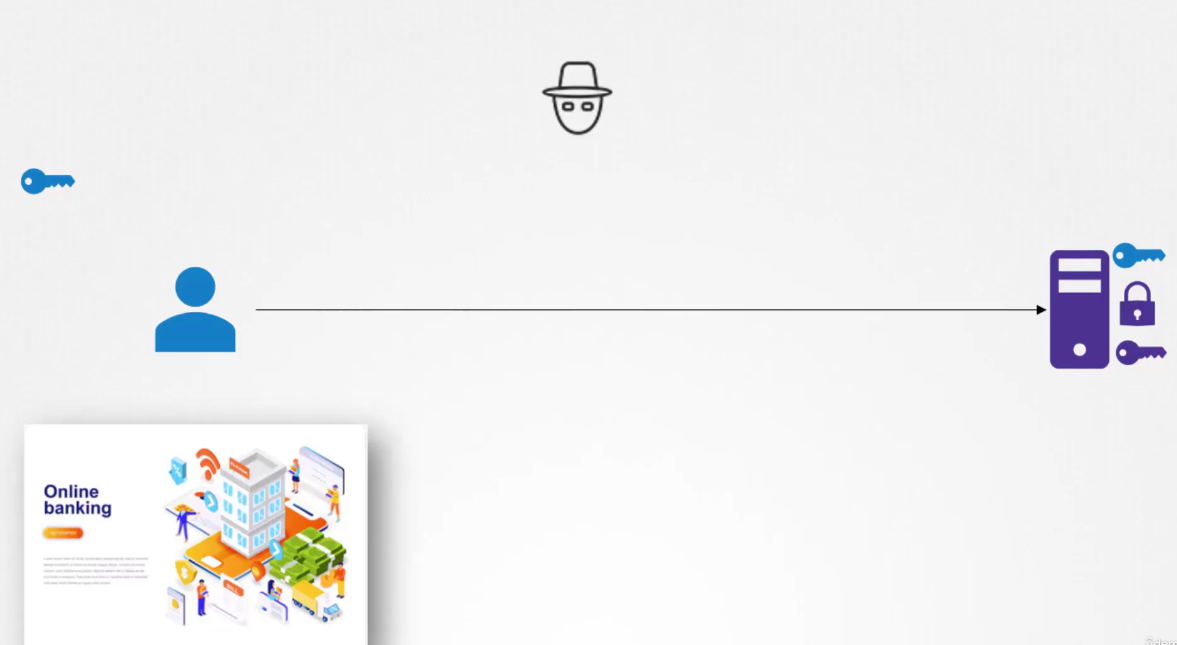

Instead of using a single key to encrypt and decrypt data,

asymmetric encryption uses a pair of keys,

a private key and a public key.

Well, they are private and public keys,

but for the sake of this example,

we will call it a private key and a public lock.

We will get back to that at the end,

but for now think of it as a key and a lock pair.

A key, which is only with me, so it’s private,

a lock that anyone can access, so it’s public.

The trick here is, if you encrypt or lock the data

with your lock, you can only open it

with the associated key.

So your key must always be secure with you

and not be shared with anyone else, it’s private,

but the lock is public and maybe shared with others,

but they can only lock something with it.

No matter what is locked using the public lock,

it can only be unlocked by your private key.

Before we go back to our web server example,

let’s look at an even simpler use case

of securing SSH access to servers using key pairs.

You have a server in your environment

that you need access to.

You don’t want to use passwords as they’re too risky

so you decide to use key pairs.

You generate a public and private key pair.

You can do this by running the SSH keys and command.

It creates two files, ID_RSA is the private key

and ID_RSA.pub is the public key.

Well, not a public key, a public lock.

You then secure your server

by locking down all access to it,

except through a door that is locked using your public lock.

It’s usually done by adding an entry with your public key

into the server’s SSH authorized_keys file.

So you see the lock is public

and anyone can attempt to break through.

But as long as no one gets their hands on your private key,

which is safe with you on your laptop,

no one can gain access to the server.

When you try to SSH, you specify the location

of your private key in your SSH command.

What if you have other servers in your environment?

How do you secure more than one server with your key pair?

Well, you can create copies of your public lock

and place them on as many servers as you want.

You can use the same private key

to SSH into all of your servers securely.

What if other users need access to your servers?

Well, they can do the same thing.

They can generate their own public and private key pairs.

As the only person who has access to those servers,

you can create an additional door for them

and lock it with their public locks,

copy their public locks to all the servers,

and now other users can access the servers

using their private keys.

Let’s go back to our web server example.

You see, the problem we had earlier

with symmetric encryption was that the key used

to encrypt data had to be sent to the server

over the network along with the encrypted data,

and so there is a risk of the hacker getting the key

to decrypt the data.

What if we could somehow get the key to the server safely?

Once the key is safely made available to the server,

the server and client can safely continue communication

with each other using symmetric encryption.

To securely transfer the symmetric key

from the client to the server,

we use asymmetric encryption.

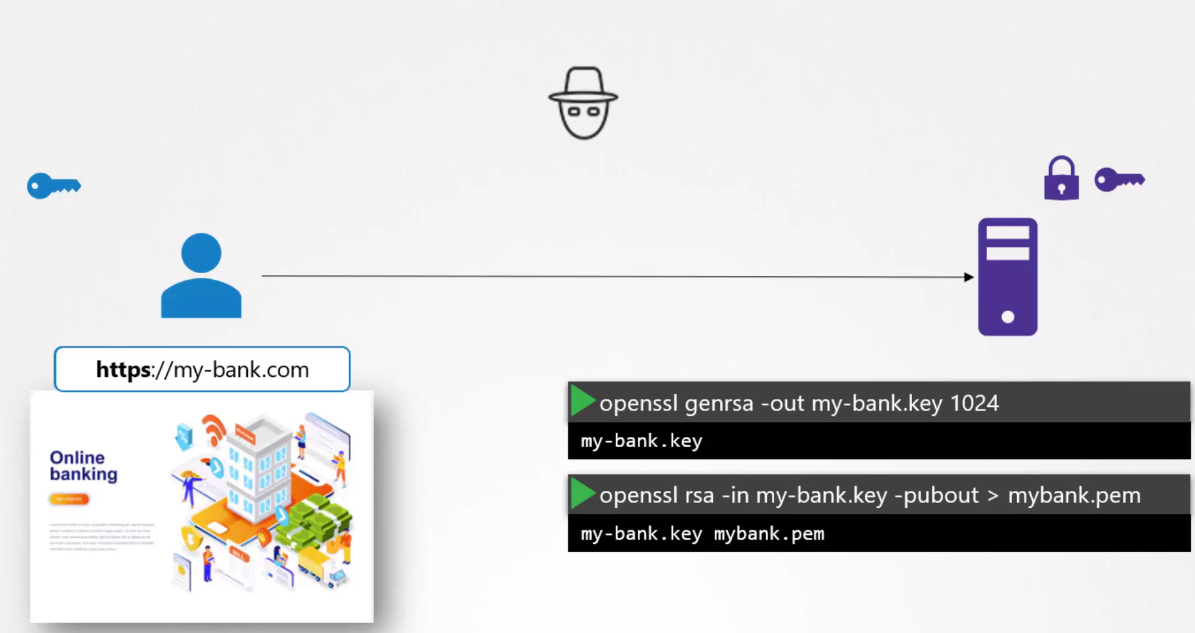

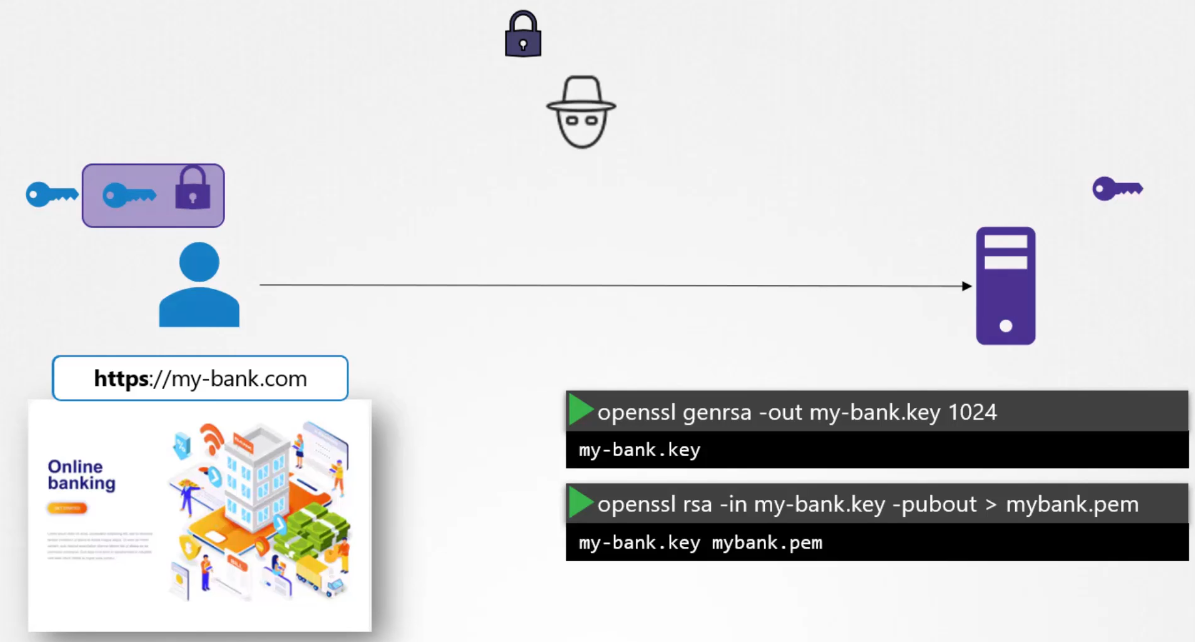

So we generate a public and private key pair on the server.

We’re going to refer to the public log

as public key going forward

now that you have got the idea.

The SSH key gen command was used earlier

to create a pair of keys for SSH purposes,

so the format is a bit different.

Here we use the open SSL command

to generate a private and public key pair,

and that’s how they look.

When the user first accesses the web server using STTPS,

When the user first accesses the web server using STTPS,

he gets the public key from the server.

Since the hacker is sniffing all traffic,

let us assume he too gets a copy of the public key.

We’ll see what he can do with it.

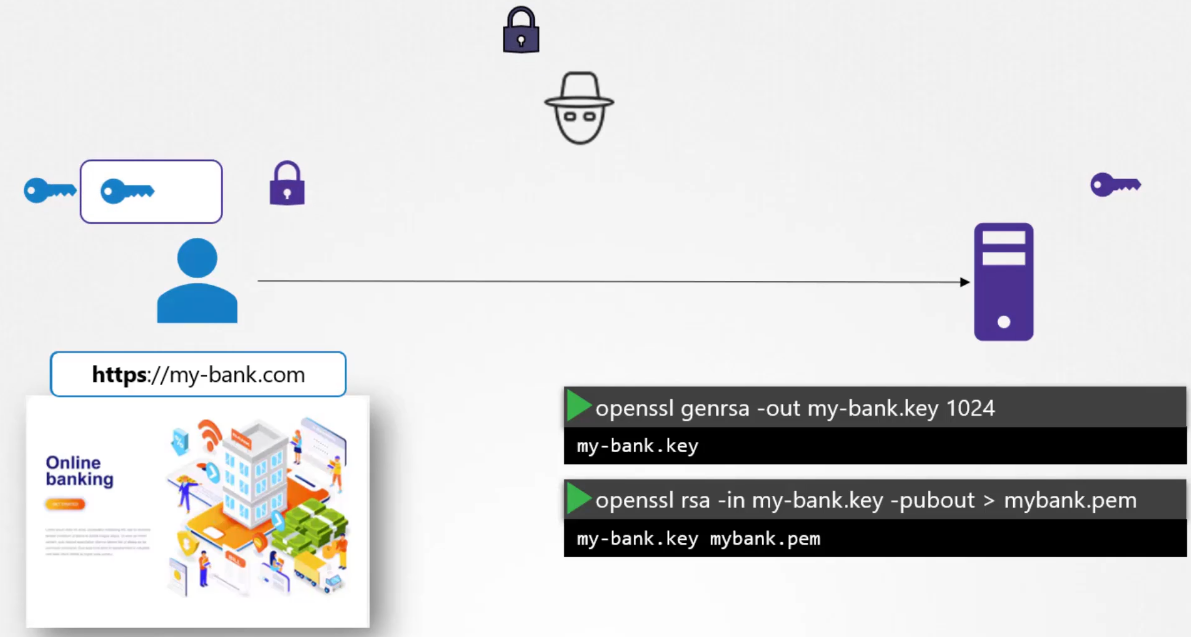

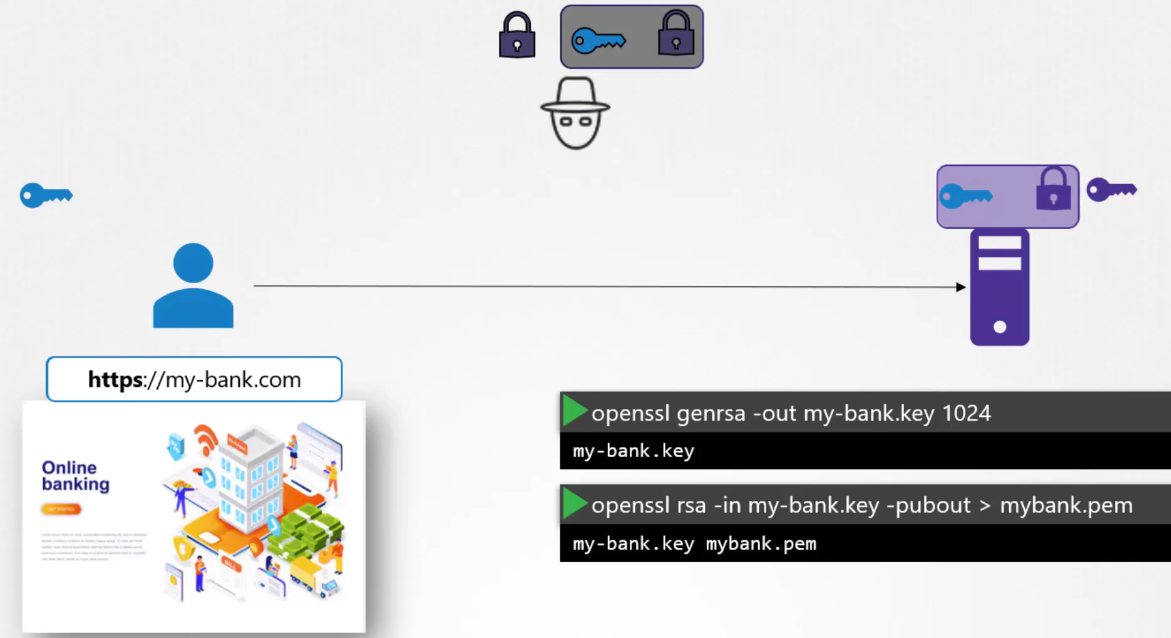

The user, in fact, the user’s browser

then encrypts the symmetric key

using the public key provided by the server.

The symmetric key is now secure.

The user then sends this to the server.

The hacker also gets a copy.

The hacker also gets a copy.

The server uses the private key to decrypt the message

and retrieve the symmetry key from it.

and retrieve the symmetry key from it.

However, the hacker does not have the private key

to decrypt and retrieve the symmetric key

from the message it received.

The hacker only has the public key

with which he can only lock or encrypt a message

and not decrypt the message.

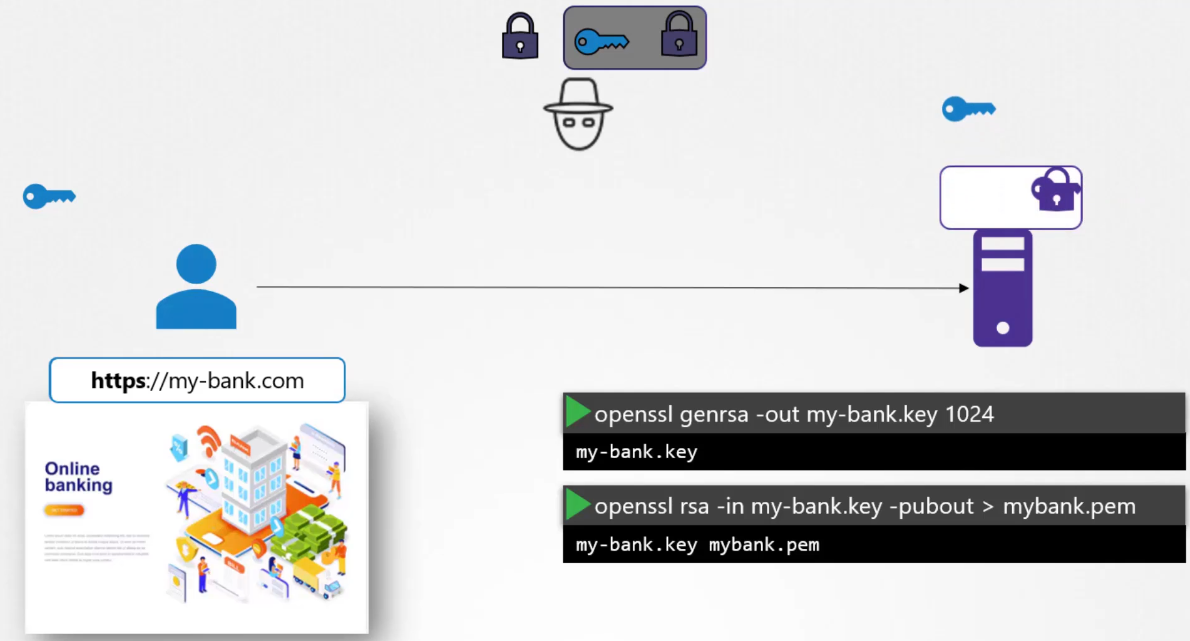

The symmetric key is now safely available only

to the user and the server.

They can now use the symmetric key

They can now use the symmetric key

to encrypt data and send to each other.

The receiver can use the same symmetric key

to decrypt data and retrieve information.

to decrypt data and retrieve information.

The hacker is left with the encrypted messages

and public keys with which he can’t decrypt any data.

With asymmetric encryption,

we have successfully transferred the symmetric keys

from the user to the server,

and with symmetric encryption

we have secured all future communication between them.

Perfect.

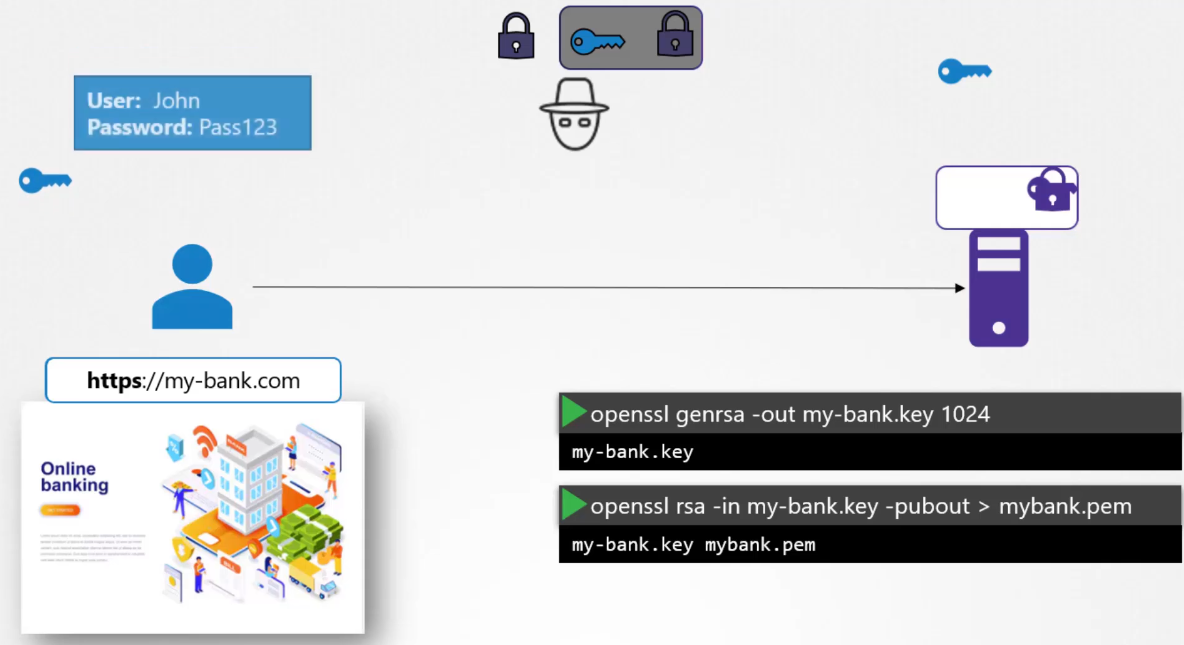

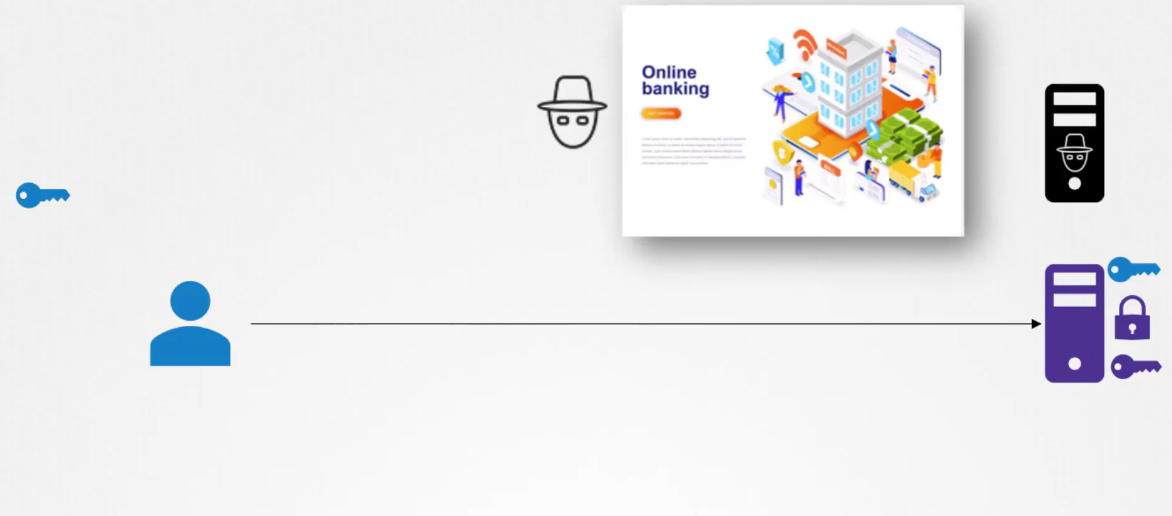

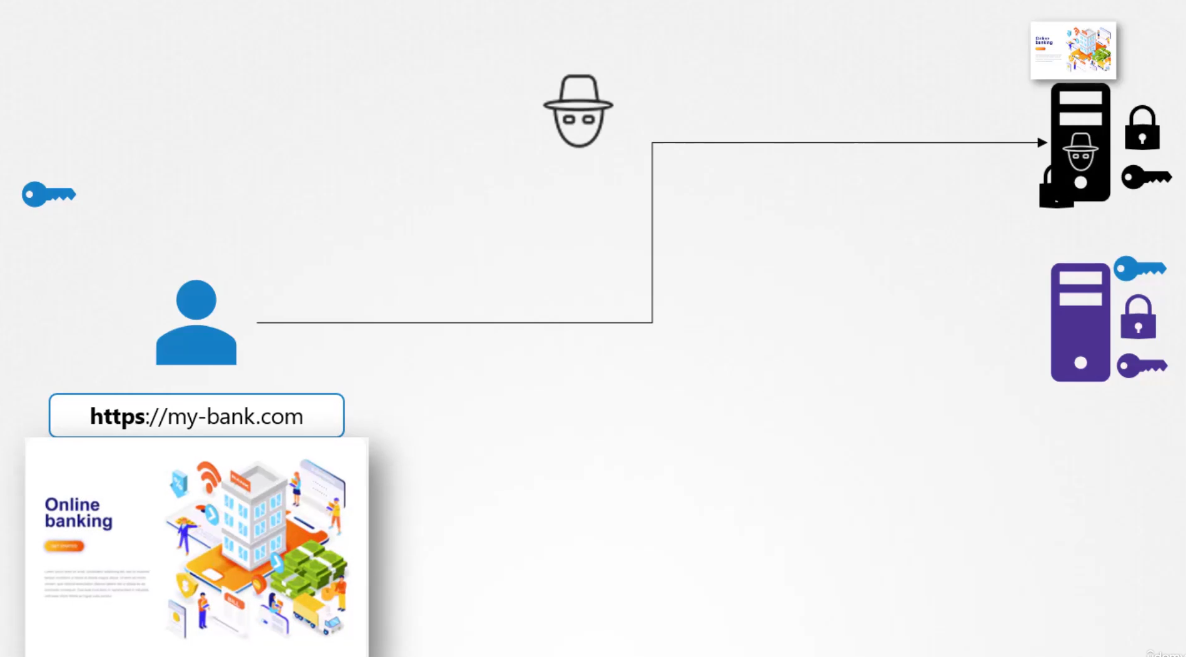

The hacker now looks for new ways to hack into your account,

The hacker now looks for new ways to hack into your account,

and so he realizes that the only way he can get your credential is by getting you

to type it into a form he presents.

So he creates a website that looks exactly

like your bank’s website.

The design is the same, the graphics are the same,

the website is a replica of the actual bank’s website.

He hosts the website on his own server.

He hosts the website on his own server.

He wants you to think it’s secure too,

so he generates his own set of public

so he generates his own set of public

and private key pairs and configures them on his web server.

And finally, he somehow manages to tweak your environment

or your network to route your request going

or your network to route your request going

to your bank’s website to his servers.

When you open up your browser

and type the website address in,

you see a very familiar page,

you see a very familiar page,

the same logging page of your bank

that you are used to seeing,

so you go ahead and type in the username and password.

You make sure you type in STPS in the URL

to make sure the communication is secure and encrypted.

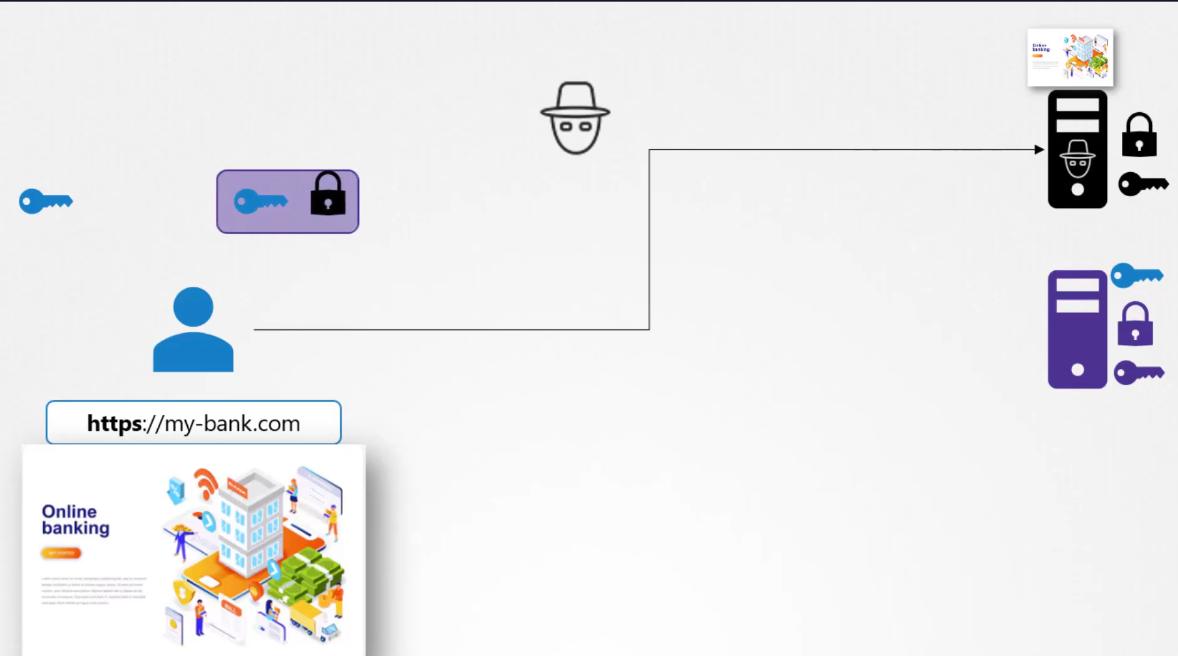

Your browser receives a key,

you send encrypted symmetric key

you send encrypted symmetric key

and then you send your credentials encrypted with the key

and the receiver decrypts the credentials

with the same symmetric key.

with the same symmetric key.

You’ve been communicating securely in an encrypted manner,

but with the hacker’s server.

As soon as you send in your credentials,

you see a dashboard that doesn’t look very much

you see a dashboard that doesn’t look very much

like your bank’s dashboard.

What if you could look at the key you received

What if you could look at the key you received

from the server and say if it is a legitimate key

from the real bank server?

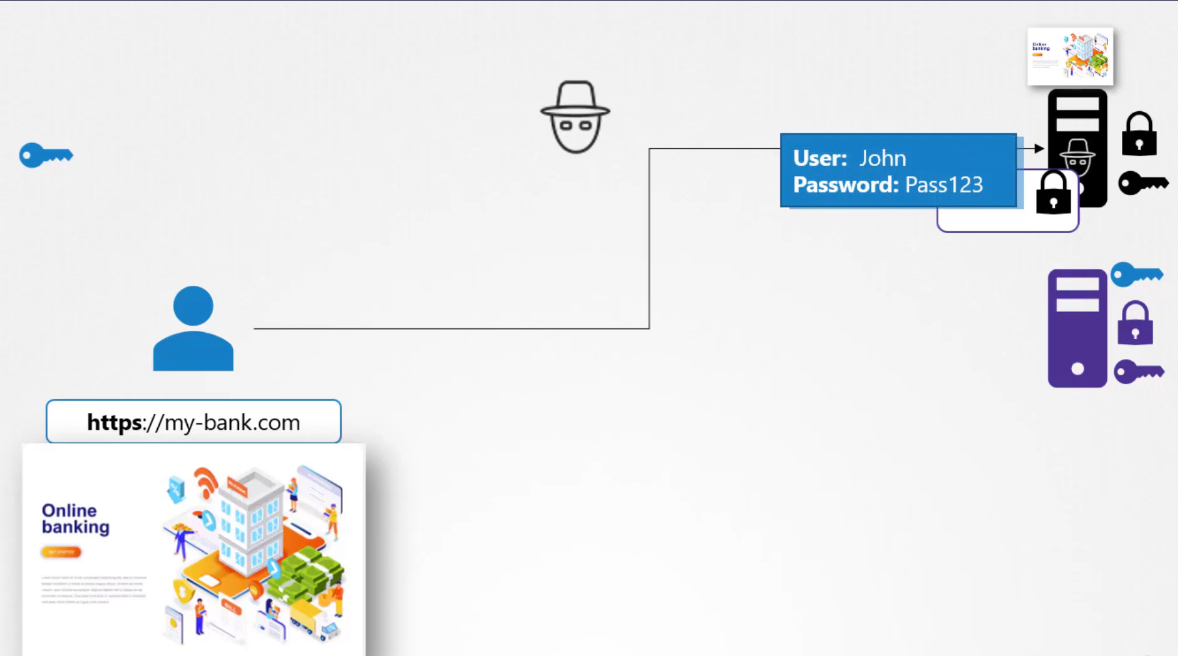

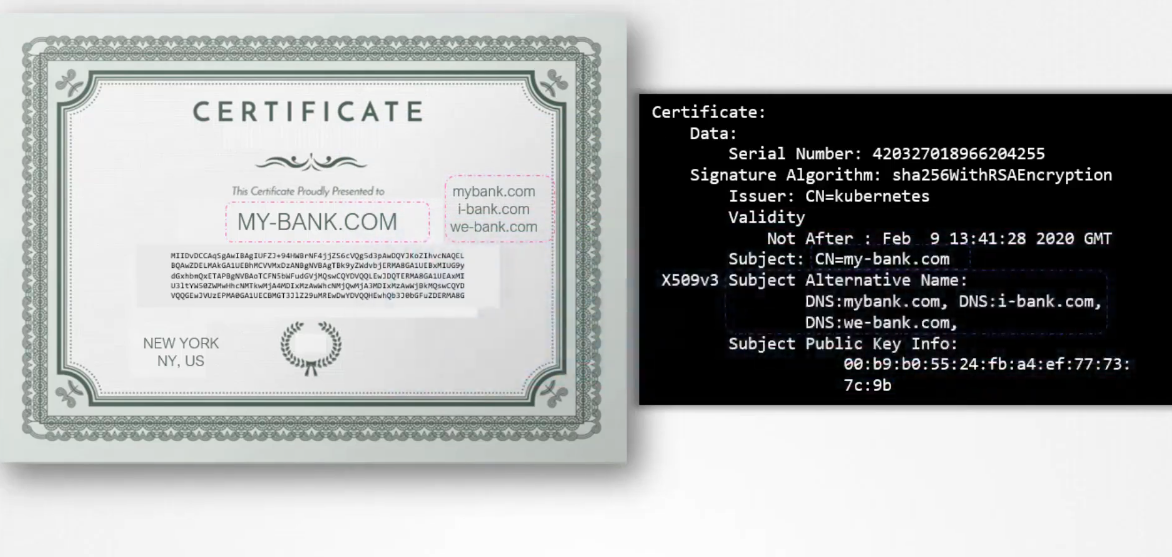

When the server sends the key,

it does not send the key along,

it does not send the key along,

it sends a certificate that has the key in it.

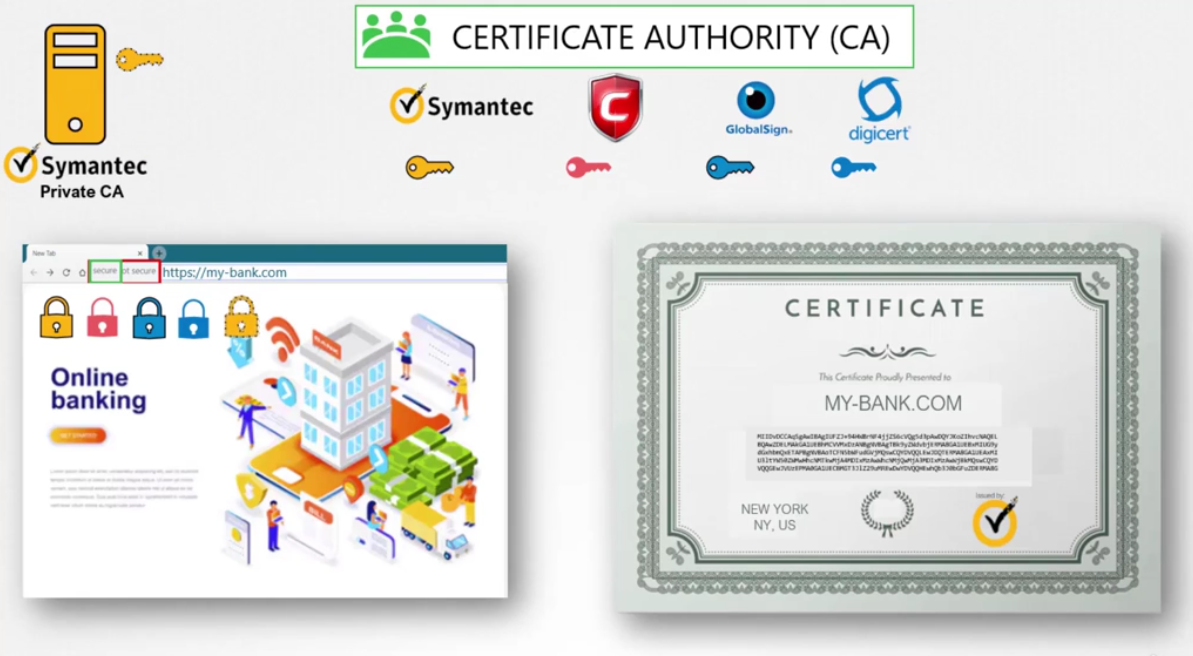

If you take a closer look at the certificate,

you will see that it is like an actual certificate

you will see that it is like an actual certificate

but in a digital format.

It has information about who the certificate is issued to,

the public key of that server,

the location of that server, et cetera.

On the right, you see the output of an actual certificate.

On the right, you see the output of an actual certificate.

Every certificate has a name on it,

the person or subject to whom the certificate

is issued to that is very important

as that is the field that helps you validate their identity.

If this is for a web server,

this must match what the user types in

in the URL on his browser.

If the bank is known by any other names,

and if they’d like their users to access their application

and if they’d like their users to access their application

with the other names as well,

then all those names should be specified in this certificate

under the subject as native name section.

But you see, anyone can generate a certificate like this.

You could generate one for yourself saying you’re Google,

and that’s what the hacker did in this case.

He generated a certificate saying he is your bank’s website.

So how do you look at a certificate and verify

if it is legit?

That is where the most important part

of the certificate comes into play.

s

Who signed and issued the certificate?

s

Who signed and issued the certificate?

If you generated a certificate

then you’ll have to sign it by yourself.

That is known as a self-signed certificate.

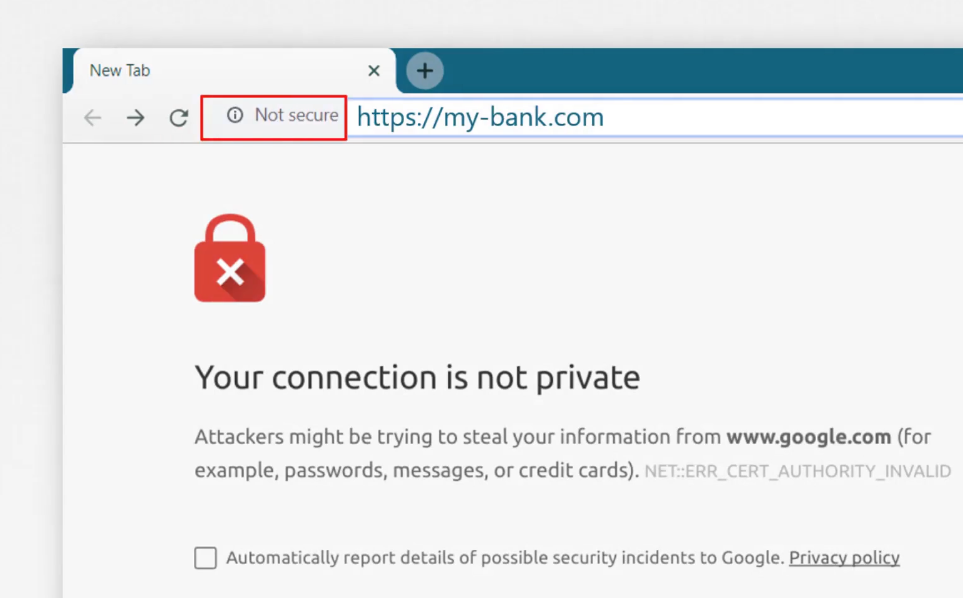

Anyone looking at the certificate you generated

will immediately know that it is not a safe certificate,

because you have signed it.

If you looked at the certificate you received

from the hacker closely,

you would’ve noticed that it was a fake certificate

that was signed by the hacker himself.

As a matter of fact, your browser does that for you.

All of the web browsers are built in

All of the web browsers are built in

with a certificate validation mechanism

while in the browser text the certificate received

from the server and validates it

to make sure it is legitimate.

If it identifies it to be a fixed certificate,

then it actually warns you.

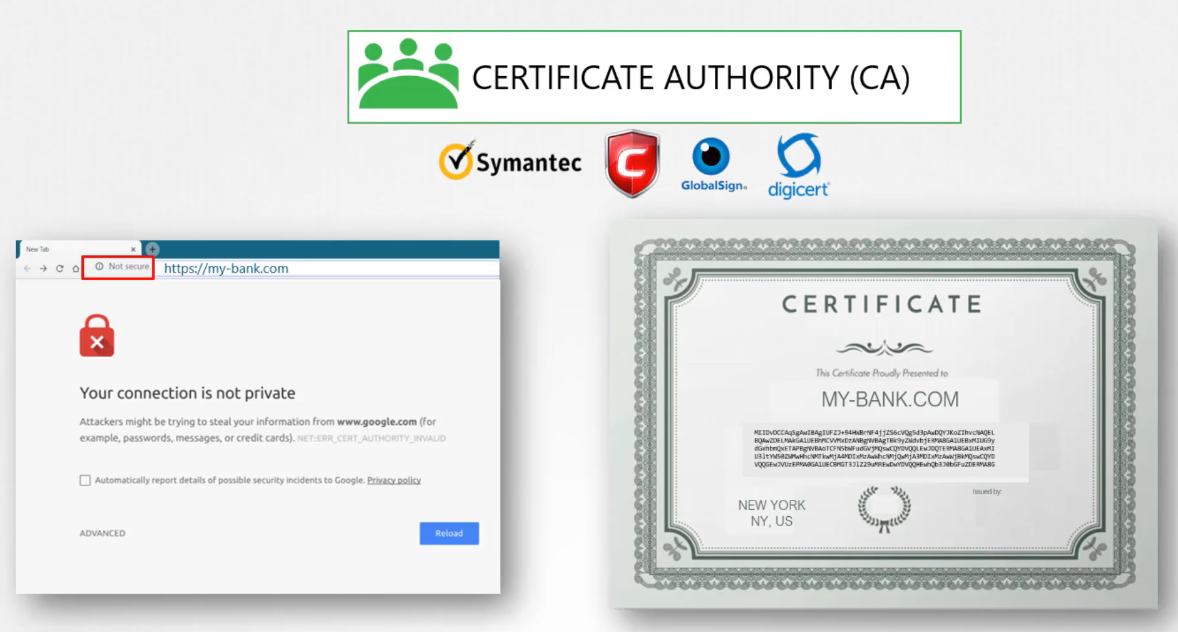

So then how do you create a legitimate certificate

for your web servers that the web browsers will trust?

How do you get your certificates signed

by someone with authority?

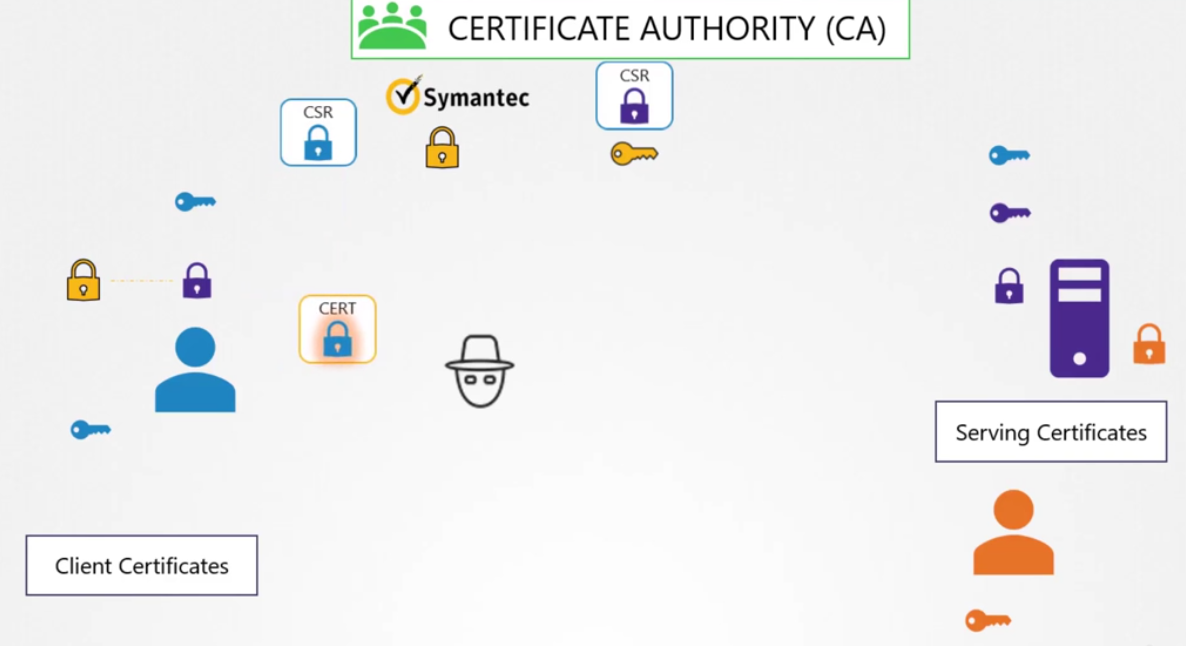

That’s where certificate authorities or CAs comes in.

That’s where certificate authorities or CAs comes in.

They’re well known organizations

that can sign and validate your certificates for you.

Some of the popular ones are Symantec, DigiCert, Comodo,

Some of the popular ones are Symantec, DigiCert, Comodo,

GlobalSign, et cetera.

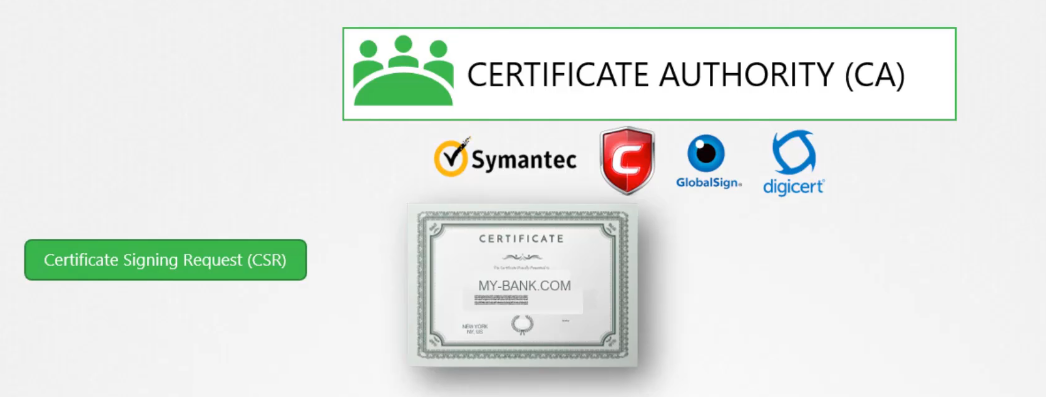

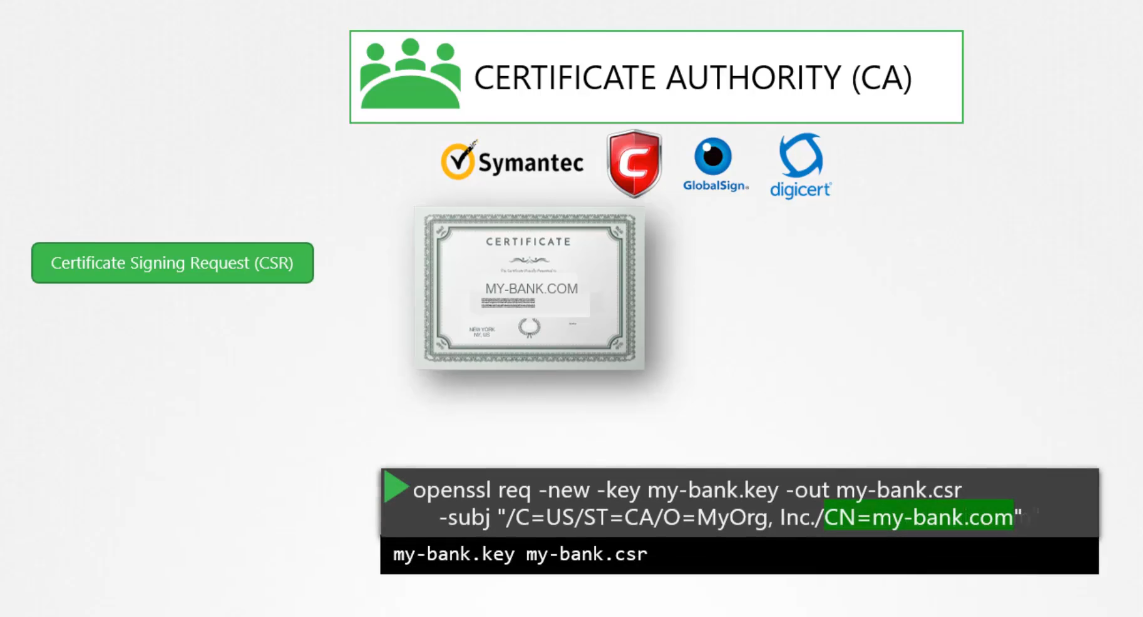

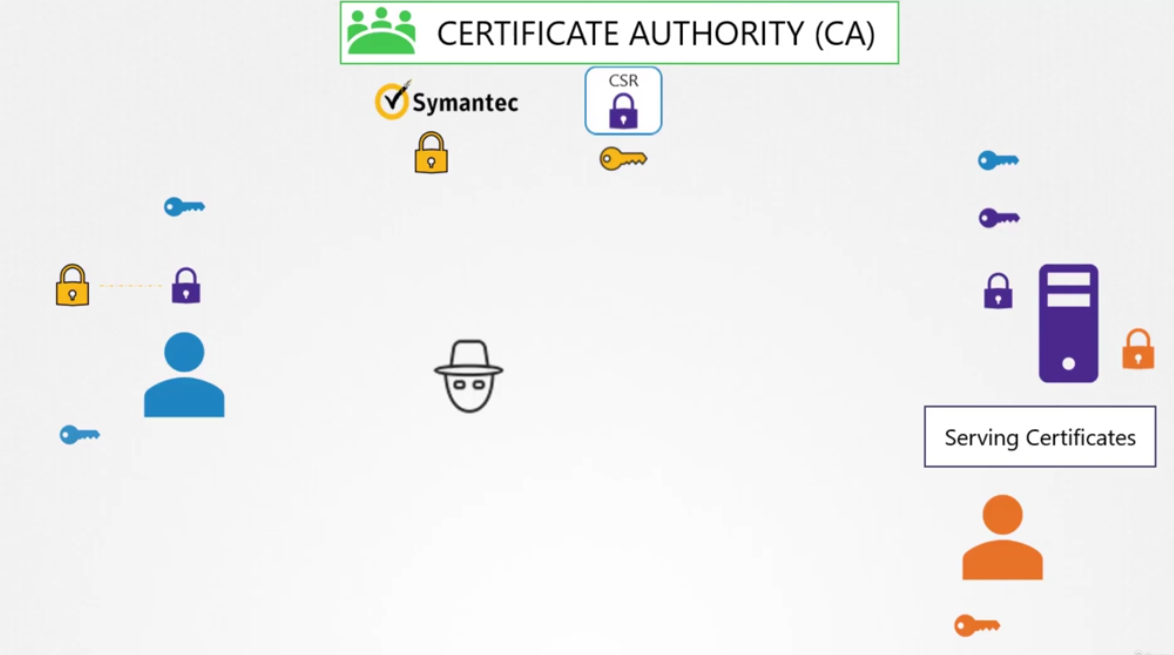

The way this works is,

you generate a certificate signing a request or CSR

you generate a certificate signing a request or CSR

using the key you generated earlier

and the domain name of your website.

You can do this again using the open SSL command.

You can do this again using the open SSL command.

This generates a My-Bank.CSR file,

which is the certificate signing request

that should be sent to the CA for signing.

It looks like this.

It looks like this.

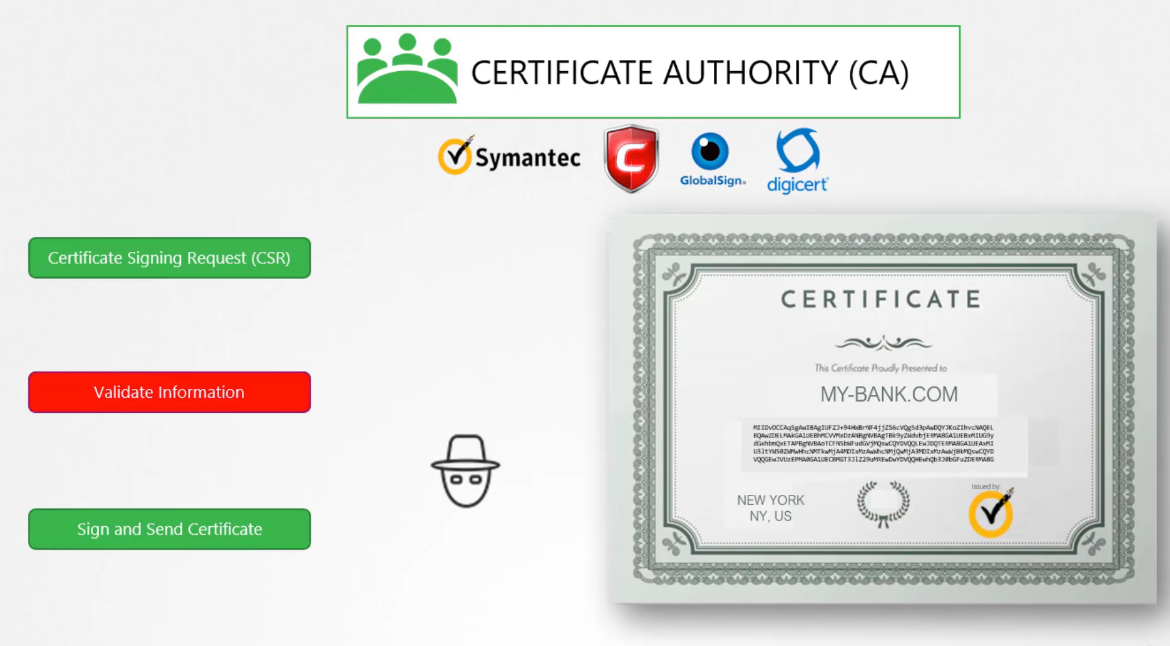

The certificate authorities verify your details

and once it checks out,

they sign the certificate and send it back to you.

they sign the certificate and send it back to you.

You now have a certificate signed by a CA

that the browsers trust.

If hacker tried to get his certificate signed the same way,

he would fail during the validation phase

he would fail during the validation phase

and his certificate would be rejected by the CA.

So the website that he’s hosting

So the website that he’s hosting

won’t have a valid certificate.

The CAs use different techniques

to make sure that you are the actual owner of that domain.

You now have a certificate signed by a CA

You now have a certificate signed by a CA

that the browsers trust.

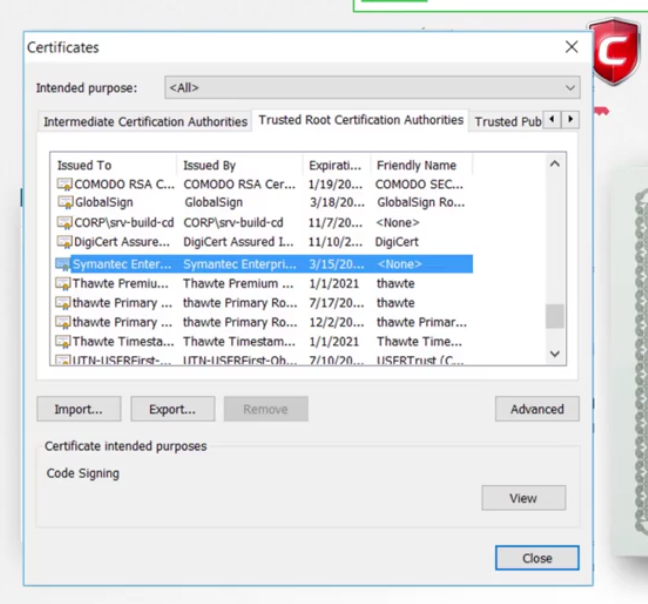

But how do the browsers know that the CA itself

was legitimate?

For example, one if the certificate was signed by a fake CA,

in this case, our certificate was signed by Symantec.

How would the browser know Symantec is a valid CA

and that the certificate was in fact signed by Symantec

and not by someone who says they are Symantec?

How CA authenticate

The CAs themselves have a set of public

The CAs themselves have a set of public

and private key pairs.

The CAs use their private keys to sign the certificates.

The public keys of all the CAs are built in to the browsers.

The browser uses the public key of the CA

to validate that the certificate was actually signed

by the CA themselves.

You can actually see them in the settings

You can actually see them in the settings

of your web browser under certificates,

they’re under trusted CAs tab.

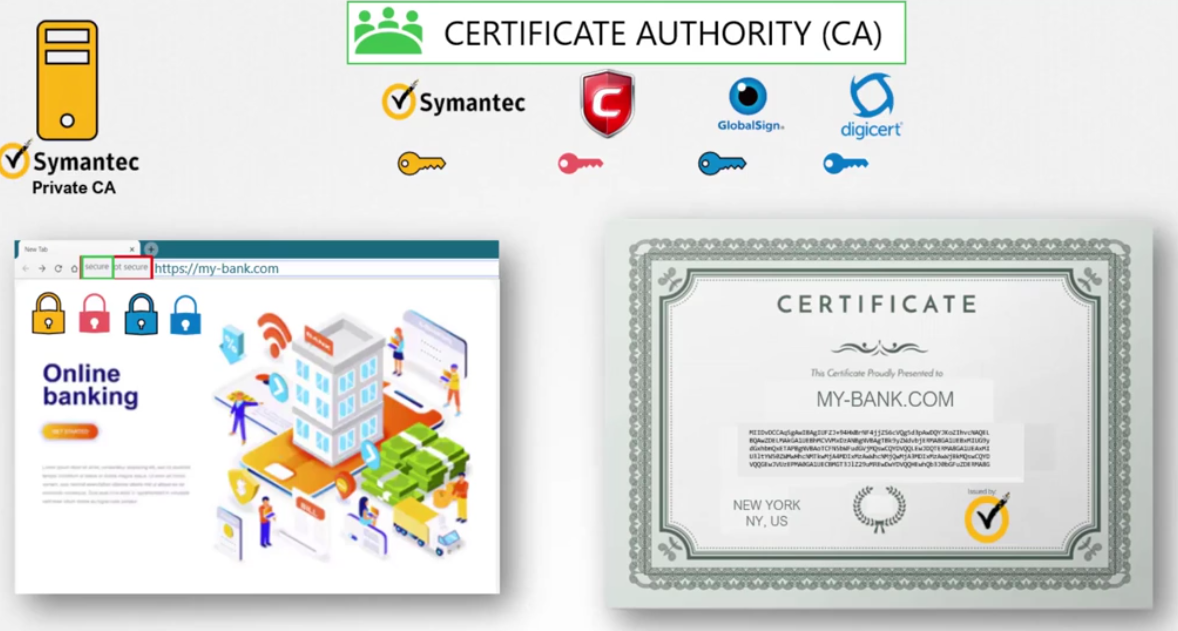

Now, these are public CAs

Now, these are public CAs

that help us ensure the public websites we visit,

like our banks, emails, et cetera, are legitimate.

However, they don’t help you validate sites

hosted privately, say within your organization.

For example, for accessing your payroll

or internal email applications.

For that, you can host your own private CAs.

For that, you can host your own private CAs.

Most of these companies listed here

have a private offering of their services,

a CA server that you can deploy internally

within your company.

You can then have the public key

You can then have the public key

of your internal CAs server installed

on all your employees browsers

and establish secure connectivity within your organization.

summary

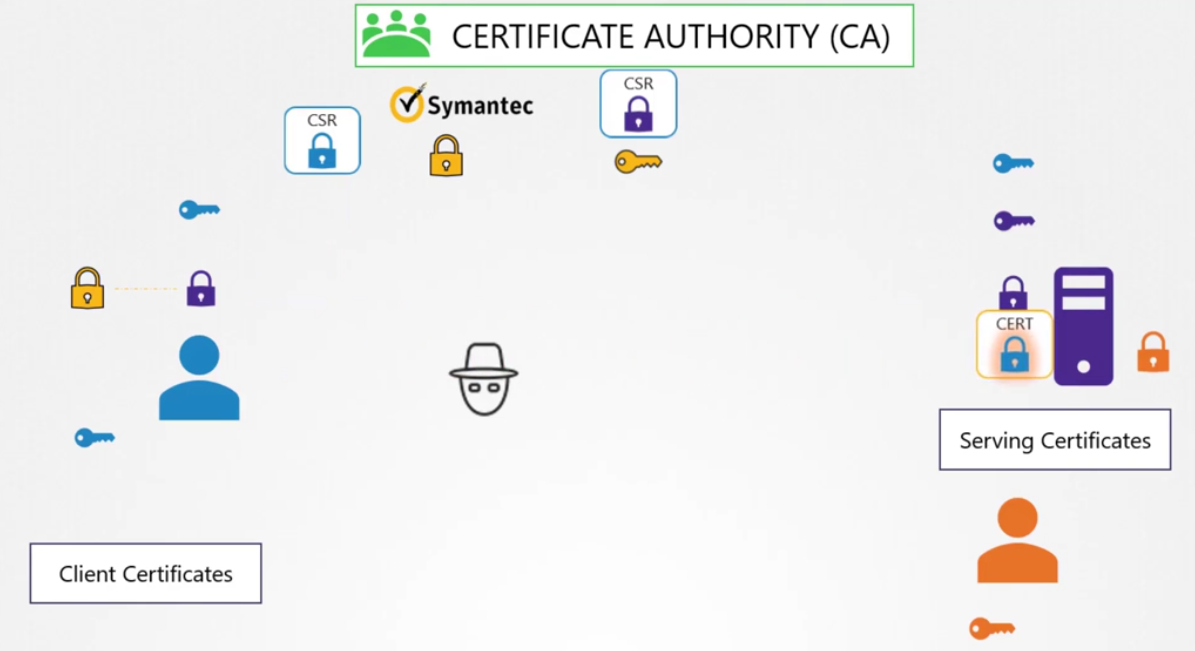

So let’s summarize real quick.

We have seen why you may want to encrypt messages

We have seen why you may want to encrypt messages

being sent over a network.

To encrypt messages, we use asymmetric encryption

with a pair of public and private keys.

An admin uses a pair of keys

to secure SSH connectivity to the servers.

The server uses a pair of keys to secure a STPS traffic.

But for this, the server first sends

a certificate signing request to a CA,

the CA uses its private key to sign the CSR.

Remember, all users have a copy of the CAs public key.

The signed certificate is then sent back to the server.

The server configures the web application

with the signed certificate.

Whenever a user accesses the web application,

the server first sends the certificate with its public key.

The user, or rather the user’s browser reads the certificate

and uses the CAs public key

to validate and retrieve the server’s public key.

It then generates a symmetric key

that it wishes to use going forward for all communication.

The symmetric key is encrypted using the server’s public key

and sent back to the server.

The server uses its private key to decrypt the message

and retrieve the symmetric key.

The symmetric key is used for communication going forward.

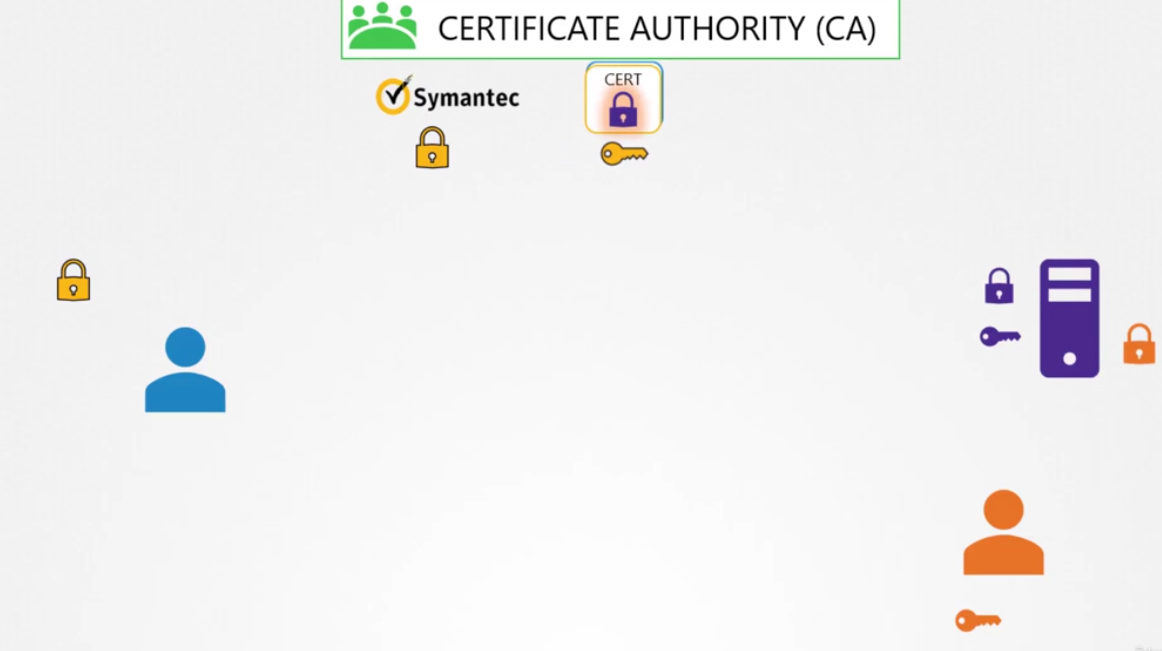

So the administrator generates a key pair for securing SSH.

The web server generates a key pair

for securing the website with STTPS.

The certificate authority generates its own set

of keeper to sign certificates.

The end user though only generates a single symmetric key.

Once he establishes trust with the website,

he uses his username and password

to authenticate to the web server.

But the server’s keepers, the client was able to validate

that the server is who they say they are,

but the server does not for sure know

if the client is who they say they are.

It could be a hacker impersonating a user

by somehow gaining access to his credentials,

not over the network for sure,

as we have secured it already with TLS,

maybe by some other means.

Anyway, so what can the server do to validate

Anyway, so what can the server do to validate

that the client is who they say they are?

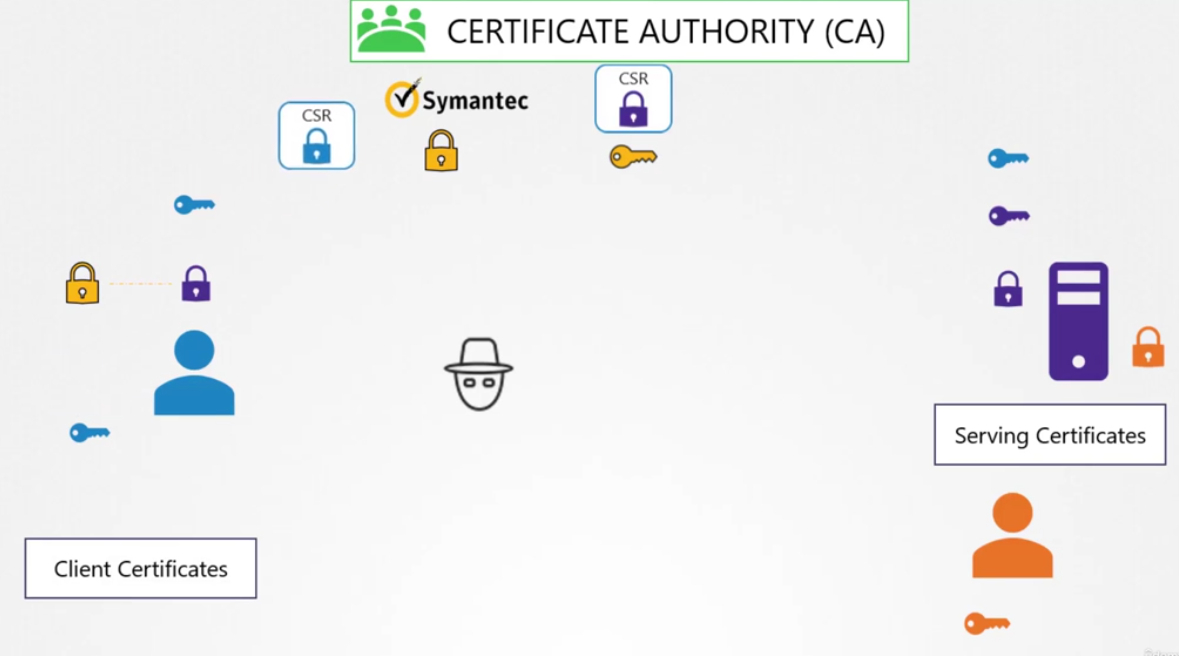

For this, as part of the initial trust building exercise,

the server can request a certificate from the client.

And so the client must generate a pair of keys

And so the client must generate a pair of keys

and a signed certificate from a valid CA.

and a signed certificate from a valid CA.

The client then sends the certificate to the server

for it to verify that the client is who they say they are.

for it to verify that the client is who they say they are.

Now, you must be thinking,

you have never generated a client certificate

to access a website.

Well, that’s because TLS client certificates

are not generally implemented on web servers.

Even if they are, it’s all implemented under the hosts.

So a normal user don’t have to generate

and manage certificates manually.

So that was the final piece about client certificates.

This whole infrastructure, including the CA,

This whole infrastructure, including the CA,

the servers, the people, and the process

of generating, distributing and maintaining

digital certificates is known as public key infrastructure

or PKI.

Finally, let me clear up something before you leave.

I been using the analogy of a key and lock

for private and public keys.

If I give you the impression that only the lock

or the public key can encrypt data,

then please forgive me as it’s not true.

These are, in fact, two related or paired keys.

You can encrypt data with any one of them

and only decrypt data with the other.

You cannot encrypt data with one and decrypt with the same.

So you must be careful what you encrypt your data with.

If you encrypt your data with your private key,

then remember anyone with your public key,

which could really be anyone out there,

will be able to decrypt and read your message.

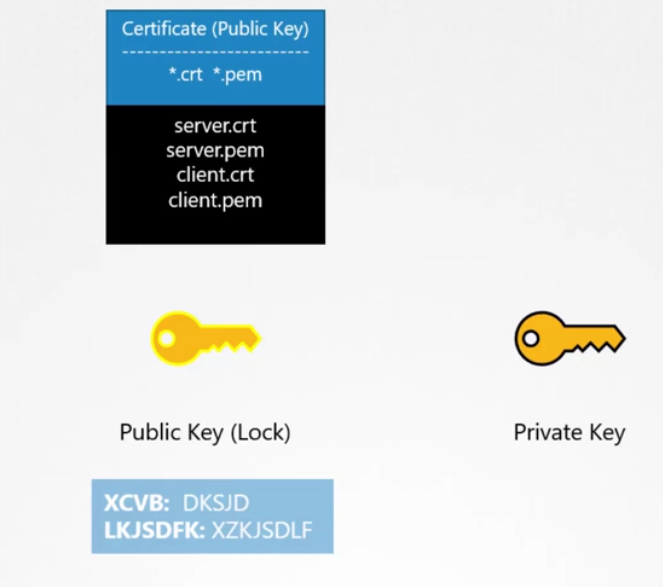

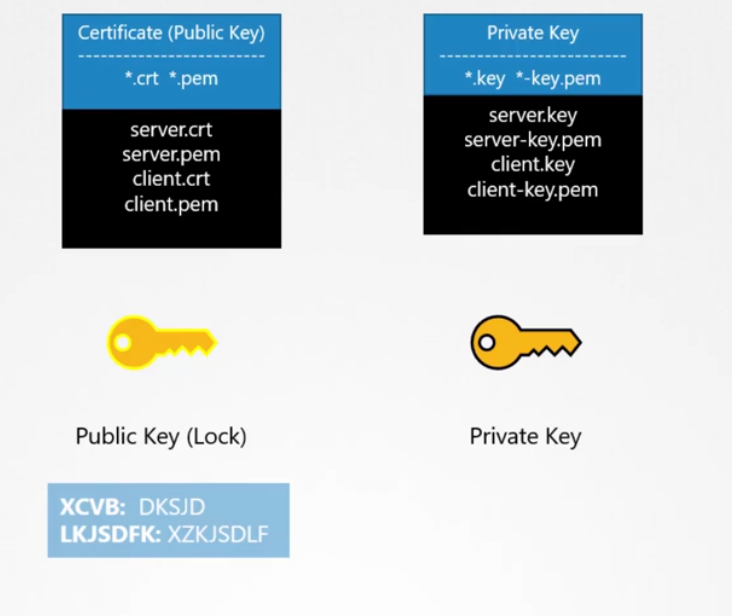

Finally, a quick note on naming convention.

Usually certificates with public key

are named crt or pem extension,

are named crt or pem extension,

so that’s server.crt, server.pem

for server certificates or client.crt,

or client.pem for client certificates.

And private keys are usually with extension .key

or -key.pem.

For example, server.key or server-key.pem.

For example, server.key or server-key.pem.

So Just remember private keys have the word key

in them usually, either as an extension

or in the name of the certificate.

And one that doesn’t have the word key in them

is usually a public key or certificate.

Well, that’s it for this lecture.

Thank you for watching.

I will see you in the next lecture.